TL;DR

For versions 9700 and above of Passwordstate, the EncryptionKey is derived differently. It now is derived by the HMAC(alg=SHA256, key=join(Secret2, Secret4), plaintext=join(Secret1, Secret3)). A PR has been made to the existing tooling which implements this.

Context

Back in 2023, I was on an internal security assessment and I had achieved Domain Admin over an on-prem Active Directory (AD) environment. To demonstrate the impact of this and to mimic what is typically performed by APTs, I decided to leverage this level of access to try and further escalate privileges or laterally move to additional IT services (backups, network infrastructure, virtualisation infrastructure, cloud services etc.). One of the most consistent ways to achieve this is to compromise the password management solution of a company, which is where I looked first.

There are various password management solutions that a given company may use, ranging from SaaS products such as 1Password and Lastpass, through to local file based password vaults such as KeePass. Some organisations elect for a middle ground between cloud hosted and local file based solutions in the form of privately hosted password management solutions. This includes services such as Bitwarden, Delinea (previously Thycotic) Secret Server and Click Studios Passwordstate. These password solutions allow a company to host their own copy of the product, so that all of the data remains within their own managed infrastructure, and thus can be configured/secured as desired. This can also be a weakness, as if these services are not configured/secured appropriately, they may allow a threat actor on the internal network to compromise sensitive secrets.

In my particular case, the client was using Passwordstate, and they (along with many other clients I’ve tested) had set up the hosted password management solution on AD domain joined infrastructure. As I had compromised the domain, I was able to gain administrative control over the Passwordstate host and its database. All I had to do was extract the passwords from the database – should be fairly straight forward, right?

Prior Research

I’m not the first person to attempt this. The folks over at NorthwaveSecurity already did some great research, which provided a way to extract and decrypt the passwords stored within the Passwordstate database. They reverse engineered Passwordstate.exe and determined the password encryption worked as follows.

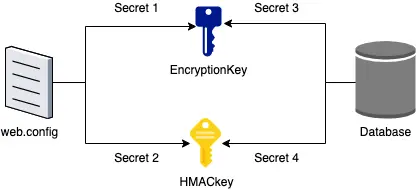

Secret1(stored inweb.config) andSecret3(stored in database) are joined together to form the EncryptionKey using Moserware Secret Splitter (a custom implementation of Shamir’s Secret Sharing Scheme).Secret2(stored inweb.config) andSecret4(stored in database) are joined together to form the HMACkey using the same technique. The HMACkey is used for verifying the integrity of the database, and is not relevant to decryption.

The diagram below demonstrates this visually (credit to NorthwaveSecurity for the diagram)

The EncryptionKey is used for encryption via the RijndaelManaged class, with a KeySize and BlockSize of 256. For this reason it’s not quite AES-256 since the block-size is 256 bits, but it’s from the same family. A random Initialisation Vector (IV) is generated and used for encryption, which is appended to the end of the resultant ciphertext.

Therefore to extract and decrypt passwords from a Passwordstate instance, the steps were as follows:

- Extract the encrypted passwords

- Extract

Secret1andSecret3to construct theEncryptionKeyusing Moserware Secret Splitter - Decrypt the passwords using the

RijndaelManagedclass with aKeySizeandBlockSizeof 256

NorthwaveSecurity built a PowerShell script that did exactly that. Alternatively, you could manually pass the required components to the script as command line arguments, such that the decryption could be performed offline, away from the target environment. This tooling worked great, and I had previously used it to recover secrets from Passwordstate databases.

In Passwordstate version 8903, the Modzero team found that Click Studios had slightly changed the cryptographic implementation, resulting in NorthwaveSecurity’s tool no longer working out of the box. As noted by Modzero, it was unclear whether this cryptographic change was done in response to the tool, or for another unrelated reason. Modzero found that the cryptographic change implemented was a simple reverse of the EncryptionKey, and made a PR.

What's New?

When attempting to use the existing tooling, I had no success. I quickly realised that Click Studios had again changed the cryptographic implementation. My guess (not verified) was that this change was introduced in Passwordstate 9.7 – Build 9700 (7th February 2023). The changelog for that version includes:

- Provided additional randomization of encryption keys

It’s again unclear whether this change was made in response to the tooling, or for another unrelated reason. Either way, if I wanted to recover the passwords from the Passwordstate database, I had to reverse engineer the new encryption implementation.

Initial Attempts

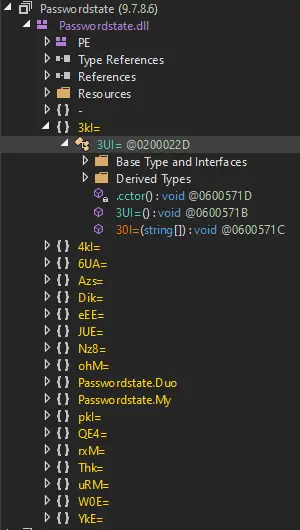

As the Modzero team had discussed, Click Studios had employed a commercial obfuscator into all of their assemblies in Passwordstate 9.3 – Build 9300 (2nd August 2021). In particular, I noted they were using Agile.NET, most likely version 6.6 (or later). As the cryptographic change occurred after the obfuscation was introduced, I could not utilise an older version of the software that didn’t have obfuscation applied like Modzero had done.

So, how hard can the obfuscation be to deobfuscate? Not-trivial it turns out (at least within the short timeframe of my internal security assessment). Opening up Passwordstate.dll in dnSpy looks like this:

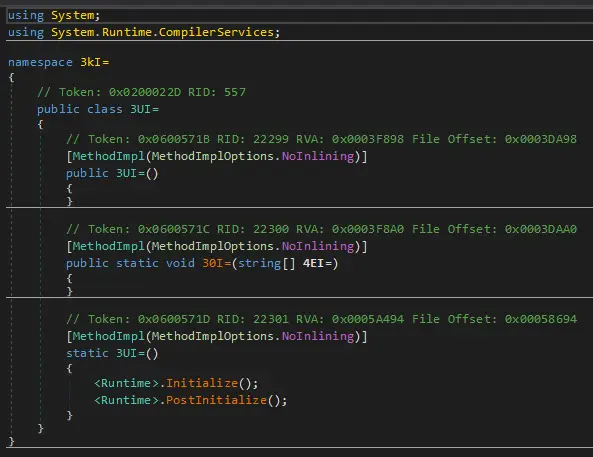

The obfuscator not only renames namespaces/classes/methods/attributes, but it also does quite a bit of work to hide the underlying assembly. For example, a typical namespace looks like this when statically decompiled:

You’ll notice that all of the functions look like they don’t do anything, except for <Runtime>.Initialize() and <Runtime>.PostInitialize(). These functions do some magic to deobfuscate and load the necessary assembly parts at runtime.

I tried some existing tooling for deobfuscating Agile.NET such as de4dot and similar projects, however none were successful. It appeared that Agile.NET 6.6 had introduced some changes that the existing tooling did not have open-source solutions for.

I eventually stumbled onto this blog post from the Computer Emergency Response Team – Agency for Digital Italy (CERT-AGID), who had reverse engineered Agile.NET 6.6 and provided some notes on how to deobfuscate it. This looked promising, however for someone not too familiar with the world of commercial obfuscation techniques, it looked like it would require a significant time-investment to try and understand and implement. Given that I was on a penetration test and time-limited, I decided to look for easier routes first, and come back to this as a last resort.

I also tried my hand at debugging the application, dumping memory etc., but again I had no luck (probably a skill issue).

Modifying .NET Core Libraries

After various failed attempts at deobfuscating/debugging the Passwordstate assemblies, I decided to go after an easier target. I knew the Passwordstate assemblies used the .NET runtime and various functions from .NET libraries, and I knew that those libraries wouldn’t be obfuscated, so why not try attacking the library functions instead? The idea being that if I can modify the .NET library functions to leak information, I might be able to make more educated guesses about how Passwordstate is operating.

It goes without saying that modifying the .NET libraries used by a Windows host is not safe and will break things, so I did this against my own local test instance of Passwordstate.

Recalling back to the previous research, it was noted that Passwordstate was using RijndaelManaged for encrypting/decrypting passwords. This class is provided by the System.Security.Cryptography namespace, and was the first target I went after. This is provided by .NET’s mscorlib (Microsoft Common Object Runtime Library) which can be found in the Global Assembly Cache (GAC). Looking at DLL imports with Procmon confirmed the following file was being imported by Passwordstate: C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\assembly\GAC_64\mscorlib\v4.0_4.0.0.0__b77a5c561934e089\mscorlib.dll. I made a copy of the DLL and opened it in dnSpy which revealed the following implementation of RijndaelManaged.

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

namespace System.Security.Cryptography

{

// Token: 0x02000357 RID: 855

[ComVisible(true)]

public sealed class RijndaelManaged : Rijndael

{

// Token: 0x0600254D RID: 9549 RVA: 0x000272EE File Offset: 0x000254EE

public RijndaelManaged()

{

if (CryptoConfig.AllowOnlyFipsAlgorithms)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException(Environment.GetResourceString( "Cryptography_NonCompliantFIPSAlgorithm"));

}

}

// Token: 0x0600254E RID: 9550 RVA: 0x0002730D File Offset: 0x0002550D

public override ICryptoTransform CreateEncryptor(byte[] rgbKey, byte[] rgbIV)

{

return this.NewEncryptor(rgbKey, this.ModeValue, rgbIV, this.FeedbackSizeValue, RijndaelManagedTransformMode.Encrypt);

}

// Token: 0x0600254F RID: 9551 RVA: 0x00027324 File Offset: 0x00025524

public override ICryptoTransform CreateDecryptor(byte[] rgbKey, byte[] rgbIV)

{

return this.NewEncryptor(rgbKey, this.ModeValue, rgbIV, this.FeedbackSizeValue, RijndaelManagedTransformMode.Decrypt);

}

// Token: 0x06002550 RID: 9552 RVA: 0x0002733B File Offset: 0x0002553B

public override void GenerateKey()

{

this.KeyValue = Utils.GenerateRandom(this.KeySizeValue / 8);

}

// Token: 0x06002551 RID: 9553 RVA: 0x00027350 File Offset: 0x00025550

public override void GenerateIV()

{

this.IVValue = Utils.GenerateRandom(this.BlockSizeValue / 8);

}

// Token: 0x06002552 RID: 9554 RVA: 0x000C04F4 File Offset: 0x000BE6F4

private ICryptoTransform NewEncryptor(byte[] rgbKey, CipherMode mode, byte[] rgbIV, int feedbackSize, RijndaelManagedTransformMode encryptMode)

{

if (rgbKey == null)

{

rgbKey = Utils.GenerateRandom(this.KeySizeValue / 8);

}

if (rgbIV == null)

{

rgbIV = Utils.GenerateRandom(this.BlockSizeValue / 8);

}

return new RijndaelManagedTransform(rgbKey, mode, rgbIV, this.BlockSizeValue, feedbackSize, this.PaddingValue, encryptMode);

}

}

}

Looking at the class, it can be seen that CreateEncryptor and CreateDecryptor both call the NewEncryptor private method, which makes it the prime candidate for modification.

I added the following code to the function to write the interesting parameters out to disk:

using System.IO;

private ICryptoTransform NewEncryptor(byte[] rgbKey, CipherMode mode, byte[] rgbIV, int feedbackSize, RijndaelManagedTransformMode encryptMode)

{

if (rgbKey == null)

{

rgbKey = Utils.GenerateRandom(this.KeySizeValue / 8);

}

if (rgbIV == null)

{

rgbIV = Utils.GenerateRandom(this.BlockSizeValue / 8);

}

using (StreamWriter streamWriter = new StreamWriter("c:\\temp\\rijndael-new-encryptor.txt", true))

{

streamWriter.WriteLine("rgbKey");

streamWriter.WriteLine(BitConverter.ToString(rgbKey).Replace("-", ""));

streamWriter.WriteLine("rgbIV");

streamWriter.WriteLine(BitConverter.ToString(rgbIV).Replace("-", ""));

streamWriter.WriteLine("encryptMode");

streamWriter.WriteLine(encryptMode);

}

return new RijndaelManagedTransform(rgbKey, mode, rgbIV, this.BlockSizeValue, feedbackSize, this.PaddingValue, encryptMode);

}

Note: this is a hack and is not production-grade code. It is not thread-safe and will break the Passwordstate service, however it was sufficient for my POC purposes.

I recompiled the DLL and attempted to replace the existing copy with my modified version (after backing up the original). Since this is the .NET framework core library’s DLL, there were lots of services and processes that had open handles on the file. Stopping all of these services (including Passwordstate, IIS Manager, Server Manager, SQL Server and more) allowed me to overwrite the legitimate copy with my modified version.

I then restarted the necessary services and waited to see the encryption key exported to disk. Nothing. Perhaps a reboot would help? Still nothing. I thought perhaps they had stopped using the RijndaelManaged class in favour of AES-256 (as per Microsoft’s recommendation), so I tried making similar modifications to the AES functions. Still nothing. I even tried making modifications to generic cryptographic functions such as CryptoStream, but no dice.

After a couple hours of debugging what was going on, I came to the conclusion that the mscorlib file I had modified wasn’t getting loaded by Passwordstate, despite the AssemblyRef table and event logs saying it was. So what gives?

It turns out that Windows was loading my file, and then loading the native image version of the DLL which is stored in the native image cache, rather than using the just-in-time (JIT) compiler to compile my modified assembly. Windows does this for improved memory and startup performance. Native image versions of assemblies can be created with Ngen.exe, however I had no luck in creating a version that took priority over the existing native image, and I had trouble uninstalling the existing native image with Ngen.exe.

To get around this, I added the COMPlus_ZapDisable environment variable and set it to 1. This environment variable forces the .NET framework to ignore the pre-compiled native images, and is intended for debugging purposes (source). I added the environment variable system-wide and accepted the performance penalty, however you should be able to achieve the same results by adding the environment variable to only the necessary processes.

Upon making this change and rebooting my test instance, I had output in my file!

C:\Users\Administrator>type c:\temp\rijndael-new-encryptor.txt

rgbKey

A5[redacted]CD

rgbIV

94[redacted]75

encryptMode

Decrypt

I then tried decrypting the passwords of my test instance using the rgbKey value as the -EncryptionKey command line parameter for NorthwaveSecurity’s tool and sure enough, it worked.

Now I just had to figure out how this key was being generated compared to previous versions of Passwordstate…

Finding the new algorithm

Given that the previous change to the encryption method was just reversing the encryption key, I tried looking for any simple transformations from the previously known algorithm’s key to the current key (e.g., XOR, transposition etc.), but I had no success. To cut to the chase, I tried looking for additional sources that resulted in changes to the encryption key. For example, if I made a change to some columns in the database, would the encryption key that got written to disk by my modified DLL be different?

Low and behold, modifying Secret2 (in web.config) and Secret4 in the database both resulted in changes to the encryption key that got exported into my temporary file. Recalling back to the existing research, these are joined together using Moserware’s Secret Splitter to form a HMAC key. I used the HMAC key to generate a HMAC of the original encryption key using the SHA256 hashing algorithm and voila, out popped the correct encryption key! The new encryption key derivation algorithm is therefore:

HMAC(alg=SHA256, key=join(Secret2, Secret4), plaintext=join(Secret1, Secret3))

The below PowerShell excerpt can be used to quickly spit out the new encryption key:

$secretsplitter = "C:\path\to\Moserware.SecretSplitter.dll"

$secret1 = ""

$secret2 = ""

$secret3 = ""

$secret4 = ""

Add-Type -Path $secretsplitter

# Join Secret1 + Secret3

$oldKey = [Moserware.Security.Cryptography.SecretCombiner]::Combine($Secret1 + "`n" + $Secret3).RecoveredTextString

$oldKeyBytes = $oldKey -split '([a-f0-9]{2})' | foreach-object { if ($_) {[System.Convert]::ToByte($_,16)}} # from Convert-HexStringToByteArray in PasswordDecryptor.ps1

# Join Secret2 + Secret4

$HMACKey = [Moserware.Security.Cryptography.SecretCombiner]::Combine($Secret2 + "`n" + $Secret4).RecoveredTextString

$HMACKeyBytes = $HMACKey -split '([a-f0-9]{2})' | foreach-object { if ($_) {[System.Convert]::ToByte($_,16)}}

# Perform HMAC-SHA256

$HMAC = New-Object System.Security.Cryptography.HMACSHA256

$HMAC.key = $HMACKeyBytes

$decryptionKey = $HMAC.ComputeHash($oldKeyBytes)

Write-Host "Decryption key is $(($decryptionKey | ForEach-Object ToString X2) -join '')"

Interlude

Everything up until this part of the blog post was done in 2023. After I drafted a blog post, I wanted to get better at reverse engineering and I had the goal of properly reverse engineering the Agile.NET obfuscation layer so that I could confidently show how the code had changed. This was good in theory, but I never got around to it. Also, there was a part of me that was embarrassed about how much of a hack my approach was to recovering the new crypto algorithm (basically just guess and check as opposed to doing the deobfuscation), and so I never published the blog post or submitted the PR. yay for imposter syndrome 🎉

Reversing the assembly

Jumping forward to 2025, I had gotten a little bit more experience reversing and I decided to revisit Passwordstate with the goal of properly reverse engineering the Agile.NET obfuscation layer. I cloned de4dot and began modifying the Agile.NET deobfuscation components. The blog post from the Computer Emergency Response Team – Agency for Digital Italy (CERT-AGID) provides most of the details needed to modify de4dot, and it was not as hard as I thought it was going to be. To summarise the changes, I modified:

- The string decryptor (convert random byte strings back into their original form)

- The method decryptor (decrypt the method bodies and patch them back into the assembly)

- The proxy/delegate handling (simplify the call trees)

Once I fixed these, I was able to statically deobfuscate the assemblies and read the partially deobfuscated code. Note that the original symbols could not be recovered, as these are renamed at the source level before compilation by Agile.NET.

Reviewing the partially deobfuscated source code, I was able to confirm that the HMAC algorithm was indeed now in use for deriving the Rijndael key. The below excerpt demonstrates one example where this new process is performed.

public static byte[] fS0=(string fi0=, byte[] fy0= = null)

{

byte[] array = new byte[0];

try

{

if (Operators.ConditionalCompareObjectEqual(HttpContext.Current.Session[ "LastActiveSessionTime"], null, false))

{

throw new Exception("Encryption-Decryption Failure");

}

if (Operators.ConditionalCompareObjectEqual(HttpContext.Current.Session["FIPSMode"], false, false))

{

using (RijndaelManaged rijndaelManaged = new RijndaelManaged())

{

rijndaelManaged.KeySize = 256;

rijndaelManaged.BlockSize = 256;

if (fy0= != null)

{

rijndaelManaged.Key = fy0=;

}

else

{

rijndaelManaged.Key = Xi0=.ni0=((byte[])HttpContext.Current.Session["EncryptionKey"]);

..snip...

private static byte[] ni0=(byte[] ny0=)

{

Xi0=.oC0=(Assembly.GetCallingAssembly());

return Xi0=.ZS0=(ny0=, (byte[])HttpContext.Current.Session["HMACKey"]);

}

...snip...

public static byte[] ZS0=(byte[] Zi0=, byte[] Zy0=)

{

byte[] array;

using (HMACSHA256 hmacsha = new HMACSHA256(Zy0=))

{

array = hmacsha.ComputeHash(Zi0=);

}

return array;

}

Threat Actors Already Know

After reversing the new algorithm properly and before publishing this blog post, I stumbled upon this Analysis of Secp0 Ransomware by Lexfo. It turns out that the Secp0 ransomware group had already deobfuscated and reversed the new key derivation function back in March of 2025. As part of this, Secp0 released:

- A tool to decrypt Passwordstate entries using the functions in

Passwordstate.dllvia reflection. - The source code they recovered by deobfuscating the

Passwordstate.dllassembly.

Given that both of these have existed online for some months now, I’d say that the new algorithm is already considered public knowledge.

Conclusion

For versions 9700 and above of Passwordstate, the EncryptionKey is derived differently. It now is derived by the HMAC(alg=SHA256, key=join(Secret2, Secret4), plaintext=join(Secret1, Secret3)). The following table best summarises the encryption methods:

| Versions | Encryption Key Derivation Method |

|---|---|

| x < 8903 | join(Secret1, Secret3) |

| 8903 <= x < 9700 | reverse(join(Secret1, Secret3)) |

| 9700 <= x | HMAC(alg=SHA256, key=join(Secret2, Secret4), plaintext=join(Secret1, Secret3)) |

Notes for defenders

This post does not discuss a vulnerability within Passwordstate, it just discusses how the key derivation process has changed for the server-side symmetric encryption of secrets. To take advantage of this knowledge, a threat actor would need to have possession of the application secrets (stored in web.config and the database), as well as access to the database contents.

Since I originally took a look in 2023, Passwordstate now strongly encourage encrypting the web configuration file with Data Protection API (DPAPI), and will prompt security administrators upon every login until this is done. This increases the difficulty of retrieving the application secrets, since you now need to have privileged code execution on the host to decrypt the DPAPI blobs.

According to the product comparison page, Hardware Security Module (HSM) support is not yet implemented. If it were to be implemented, this would be another way to increase the difficulty of recovering application secrets.

Passwordstate is designed in such a way that the server itself needs to be able to decrypt credentials, similar to Delinea Secret Server (server-side symmetric encryption). Moving to a zero-knowledge encryption implementation (e.g., Bitwarden / 1Password etc.) would require a large refactoring of the codebase and fundamentally change how the product is used and supported. Modzero raised this architecture choice as a finding in their previous disclosure (finding 2.3), and Click Studios advised Modzero that they would not address that specific finding.

If you’re using Passwordstate, you should focus on encrypting the application secrets with DPAPI and most importantly, preventing a threat actor from getting access to the Passwordstate server or it’s database in the first place. I typically recommend organisations move their enterprise password managers off of domain joined infrastructure, ideally onto a standalone server or if necessary, a separate management AD deployment. This prevents you from being one Active Directory exploit (0-day/n-day/misconfiguration) away from a low-privileged user taking full control of both your AD deployment and your enterprise password management solution (and thus any services whose secrets are stored in the enterprise password manager).

Coming up next time

With access to the partially deobfuscated source code, I decided to take a super quick skim over some unauthenticated code paths to see if there was anything interesting. In the next post I’ll take a look at an authentication bypass that would allow a threat actor within network range to gain complete administrative control over the application (CVE-2025-59453).